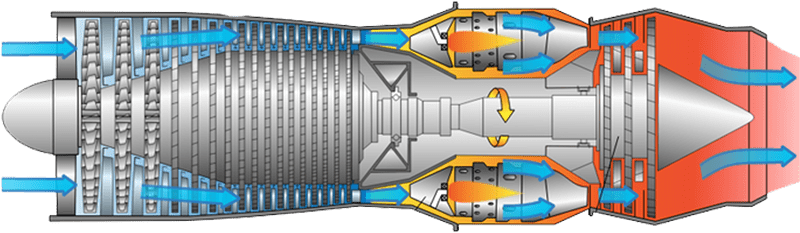

Natural gas is burned to produce mechanical energy – usually in a gas turbine — which is then converted into electrical energy that can be distributed for use in homes, businesses, and industries. This is called “gas-to-power”.

Gas can play a critical role in providing flexible, rapid energy supply, particularly when there are unexpected changes in supply and demand. As more variable forms of renewable energy are integrated into South Africa’s power grid, the need for flexible, dispatchable capacity becomes even more critical.

There are three capacity factor archetypes for gas-to-power: peaking, mid merit and baseload:

At the moment, though, the sector in South Africa is under-developed and more work needs to be done to see how much additional gas is needed to ensure that the supply is “bankable” due to typically high variable costs.

The role that gas-to-power plays in the future power sector (peaking, mid-merit, or baseload) will depend on its technical, economic, and environmental features.

In the future, we might be able to switch gas power plants to use green hydrogen instead of natural gas. This change could help us meet our goals for reducing carbon emissions to net zero. Green hydrogen is made using renewable energy, so it doesn’t produce carbon pollution, making it a cleaner alternative.

Gas turbines have a high availability factor – more than 90%, in most cases – and no restriction on output duration. This makes them more flexible and efficient than other sources.

Gas-to-power facilities have very quick ramp rates and are able to supply power at short notice. Gas turbines also have relatively low fixed costs when compared to renewables and coal, but high variable costs – particularly the gas itself. And emissions? Although gas is a fossil fuel like diesel and coal, emissions from gas are 25% lower than diesel and 60% lower than coal.

The advantages of gas-to-power systems include relatively lower emissions of pollutants compared to coal and diesel, high efficiency, and the ability to quickly ramp up and down to meet changing electricity demands.

Scaling up gas could increase our energy security and reduce our greenhouse gas emissions, but it will be an expensive exercise and a clear minimum demand required to ensure commercial viability of gas supply is required.

We need a clearer sense of what the options are for expansion, and how this will affect the broad supply of power. We will also need to look at the commercial viability including the long-term prospects for gas-to-power such a move from natural gas to green hydrogen.

Today South Africa consumes ~180 Petajoules (PJ) per annum of gas, mainly in the synthetic fuels sector.

Currently, gas demand is clustered in Gauteng, Mpumalanga and KwaZulu-Natal.

Taking a multi-sectoral lens, meaning using gas for industry, transport, synfuels and electricity, South Africa’s gas demand could range from 270 – 480 PJ per year by 2034.

The Pande and Temane gasfields, operated by Sasol in Mozambique, are South Africa’s only major gas supply today (via the ROMPCO pipeline). This supply is at risk with reserves declining from 2026.

There are several options for further gas supply, including domestic gas (onshore and offshore), regional gas and imported Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) in South Africa. Each of these options must be assessed on merit requiring thorough evaluation based on environmental, economic, and logistical factors to determine their suitability for South Africa’s energy needs.

We have limited gas-to-power capacity: Eskom runs four open-cycle gas turbines and there are two independent plants: one in the Eastern Cape and a second in KwaZulu Natal, but they are all diesel-fired at this stage.

South Africa’s electricity supply is going to be less flexible – in other words, harder to change or adapt – as coal-fired power stations are decommissioned and wind and solar rollout is accelerated.

As a larger share of daytime power is provided by solar, the power system will need additional flexibility in mornings and evenings, provided by storage (pumped hydro, battery electric) or flexible thermal plants.

The role that gas-to-power plays in the future power sector (peaking, mid-merit, or baseload) is going to depend on its technical, economic, and environmental features: how flexible and efficient the supply could be, the balance between low fixed costs and high variable costs, and its emissions profile. Gas could be used to #energisemzansi, we just need to do more work on understanding it’s potential role in the integrated energy system.

Let’s discuss the possibilities of gas and

#EnergiseMzansi

Physical Address:

12 Desmond Street,

Kramerville, 2090, South Africa

Enquiries:

Email: info@energycouncil.org.za

© 2025 Energy Council of South Africa.

All rights reserved | Privacy Policy | Fraud and Unethical Conduct

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

A Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) is a long-term contract between a buyer and a supplier of electricity that defines the terms of the agreement.

Multi-market system – a hybrid market model designed to accommodate various defined transactions (market transactions, physical bilateral transactions and regulated transactions).

Scheduling supply to meet current demand for electricity

Electricity storage encompasses all technologies that can consume electricity (e.g., charge in times of oversupply) and return it later (e.g., discharge in times of undersupply).

The capacity factor is the ratio of the actual electrical energy output over a certain period of time to the maximum possible output if the power source was operating at full capacity all the time. Essentially, it illustrates the efficiency and dependability of an energy source.

A transmission grid is an interconnected network of electrical transmission lines that moves electricity from power plants to distribution systems and end users

Variable renewable energy (VRE) or intermittent renewable energy sources (IRES) are renewable energy sources that are not adjustable due to their fluctuating nature, such as wind power and solar power

Capital costs are fixed, one-time expenses incurred on the purchase of equipment used in the production of goods

The cost added by producing one additional unit of a product or service.

Renewable energy refers to energy generated from a source that is not depleted when used

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is natural gas that has been cooled down to liquid form for ease and safety of non-pressurized storage or transport.

Republic of Mozambique Pipeline Investments Company

A petajoule (PJ) is a unit of energy measurement that is equal to one million billion joules (10 to the power 15). It can also be expressed as 278 gigawatt hours. One petajoule is equal to 31.60 million cubic meters of natural gas.

Dispatchable generation refers to sources of electricity that can be programmed on demand at the request of power grid operators, according to market needs. Dispatchable generators may adjust their power output according to an order.

Domestic gas is natural gas found underground within a county’s borders

Energy Availability Factor (EAF) = measure of generation performance, electricity available to be generated. EAF is the difference between the maximum availability and all unavailabilities expressed as a percentage

Particulates are microscopic particles of solid or liquid matter suspended in the air. Sources of particulate matter can be natural or anthropogenic. They have impacts on climate and precipitation that adversely affect human health, in ways additional to direct inhalation.

Nitric oxide (NO) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) are two gases whose molecules are made of nitrogen and oxygen atoms. These nitrogen oxides contribute to the problem of air pollution, playing roles in the formation of both smog and acid rain. They are released into Earth’s atmosphere by both natural and human-generated sources.

Sulfur oxides are a group of molecules made of sulfur and oxygen atoms, such as sulfur dioxide (SO2) and sulfur trioxide (SO3). Sulfur oxides are pollutants that contribute to the formation of acid rain, as well as particulate pollution. Some are released into Earth’s atmosphere by natural sources, but most are the result of human activities.

Net Zero means cutting carbon emissions to a small amount of residual emissions that can be absorbed and durably stored by nature and other carbon dioxide removal measures, leaving zero in the atmosphere.

Nationally Determined Contributions are the commitments that countries make to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions as part of climate change mitigation.

The Paris Agreement is a legally binding international treaty on climate change. It was adopted by 196 Parties at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP21) in Paris, France, on 12 December 2015.

The energy trilemma is a framework that energy policymakers use to balance three objectives:

likely to receive funding

The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is the EU’s tool to put a fair price on the carbon emitted during the production of carbon intensive goods that are entering the EU, and to encourage cleaner industrial production in non-EU countries

An integrated system brings together several elements to create single cohesive unit

Green hydrogen is hydrogen produced by the electrolysis of water, using renewable electricity. Production of green hydrogen causes significantly lower greenhouse gas emissions than production of grey hydrogen, which is derived from fossil fuels without carbon capture.